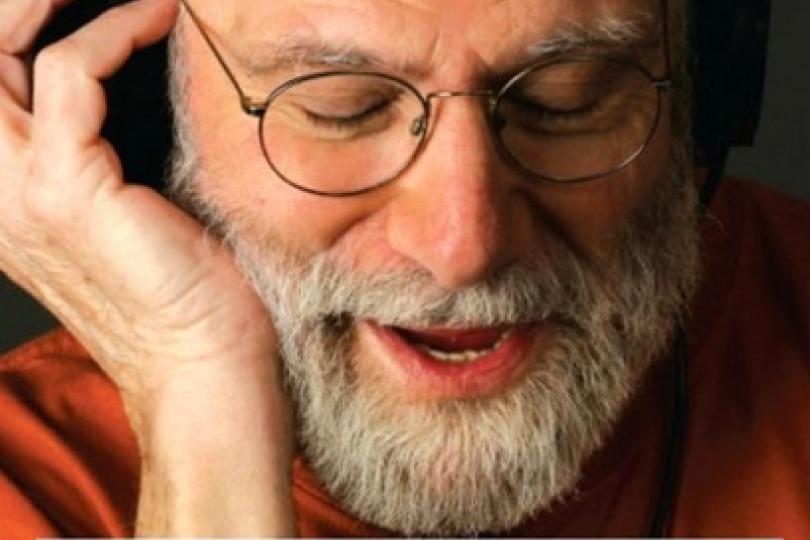

Creative Limits - Beyond the Boundaries This is a mashup of what we did this Tuesday at The Cabin's Free Drop In Writing Workshop and the workshop I brought to the inaugural Puget Sound Workshop Workshop last week. I included the reading from the Drop In and reintroduced the interdisciplinary art focus from PSWW (an absolutely incredible experience, by the way -- and they just opened up registration for 2018!). Objective: We will investigate our personal limits as creative people, and then utilize those limits and additional boundaries as an avenue to generate new artistic material across disciplines that breaks our expectations. Intro: I believe our limits help show us who we are as artists and people. Working within boundaries breaks open creativity. Our failures shape our greatest art and our mistakes create the style that makes our work stand on its own. This workshop inquiry came about following the enforced stillness and silence this spring brought about from acute laryngitis wiping out my voice and an oncoming car wiping me and mobility out on my bicycle. Those sudden informing limits gave me intense frustration and some all-too familiar depression as I couldn't get everything done I wanted to when I had hoped for a productive spring, but also got my inner resources simmering on the value of such restrictions. Read/Discuss Oliver Sacks' excerpt: Recently I read Oliver Sacks' fascinating study on music and the brain, Musicophelia. Many of his essays deal with intensive, sudden limits thrust on people that resulted in unexpected change. This one deals with musicians facing dystonia, which is a condition much like an intensive writer’s cramp caused by repetitive movement that prevents musicians from playing – sometimes for life. Sacks says: “The term ‘dystonia’ had long been used for certain twisting and posturing spasms of the muscles such as torticollis. It is typical of dystonias, as of Parkinsonism, that the reciprocal balance between agonistic and antagonistic muscles is lost, and instead of working together as they should—one set relaxing as the others contract—they contract together, producing a clench or spasm.” Here's a focus on one particular affected musician: From Athletes of the Small Muscles: Musician’s Dystonia By Oliver Sacks Recently Leon Fleisher came to visit me a few days before he was to give a performance at Carnegie Hall. He spoke of how his own dystonia had first hit him. “I remember the piece that brought it on,” he began, and described how he had been practicing the Shubert Wanderer Fantasy for eight or nine hours a day. Then he had to take an enforced rest—he had a small accident to his right thumb and could not play for a few days. It was on his return to the keyboard after this that he noticed the fourth and fifth fingers of that hand starting to curl under. His reaction to this, he said, was to work through it, as athletes are often told to “work through” the pain. But “pianists,” he said, “should not work through pain or other symptoms. I warn other musicians about this. I warn them to treat themselves as athletes of the small muscles. They make extraordinary demands on the small muscles of their hands and fingers.” In 1963, however, when the problem first arose, Fleisher had no one to advise him, no idea what was happening to his hand. He forced himself to work harder, more and more effort was needed as other muscles were brought into play. Bu the more he exerted himself, the worse it became, until finally, after a year, he gave up the struggle. “When the gods go after you,” he said, “they really know where to strike.” He had a period of deep depression and despair, feeling his career as a performer was over. But he had always loved teaching, and now he turned to conducting as well. In the 1970s, he made a discovery—in retrospect, he is surprised he did not make it earlier. Paul Wittgenstein, the dazzlingly gifted (and immensely wealthy) Viennese pianist who had lost his right arm in the Great War, had commissioned the great composers of the world—Prokofiev, Hindemith, Ravel, Strauss, Korngold, Britten, and others—to write piano solos and concertos for the left hand. And this was the treasure trove that Fleisher discovered, one that enabled him to resume him to resume his career as a performing artist—but now, like Wittgenstein and Graffman, as a one-handed pianist. Playing only with the left hand at first seemed to Fleisher a great loss, a narrowing of possibilities, but gradually he came to feel that he had been “on automatic,” following a brilliant but (in a sense) one-directional course. “You play your concerts, you play with orchestras, you make your records…that’s it, until you have a heart attack on stage and die.” But now he started to feel that his loss could be “a growth experience.” “Suddenly I realized that the most important thing in my life was not playing with two hands, it was music…In order to be able to make it across these last thirty or forty years, I’ve had to somehow de-emphasize the number of hands or the number of fingers and go back to the concept of music as music. The instrumentation becomes unimportant, and it’s the substance and content that takes over.” And yet, throughout those decades, he never fully accepted that his one-handedness was irrevocable. “The way it came upon me, “he thought, might be the way it would leave me.” Every morning for thirty-odd years, he tested his hand, always hoping. Though Fleisher had met Mark Hallett and tried Botox treatments in the late 1980s, it seemed that he needed an additional mode of treatment, in the form of Rolfing to soften up the dystonic muscles in his arm and hand—a hand so clenched that he could not open it and an arm “as hard as petrified wood.” The combination of Rolfing and Botox was a breakthrough for him, and he was able to give a two-hand performance with the Cleveland Orchestra in 1996 and a solo recital at Carnegie Hall in 2003. His first two handed recording in forty years was entitled, simply Two Hands. Botox treatments do not always work; the dose must be minutely calibrated or it will weaken the muscles too much, and it must be repeated every few months. But Fleisher had been one of the lucky ones, and gently, humbly, gratefully, cautiously, he has returned to playing with two hands—though never forgetting for a moment that, as he puts it, “once a dystonic, always a dystonic.” Fleisher now performs once again around the world, and he speaks of this return as a rebirth, “a state of grace, of ecstasy.” But the situation is a delicate one. He still has regular Rolfing therapy and takes care to stretch each finger before playing. He is careful to avoid provocative (“scaley”) music, which may trigger his dystonia. Occasionally, too, he will “redistribute some of the material,” as he puts it, modifying the fingering, shifting what might be too taxing for the right hand to the left hand. At the end of our visit, Fleisher agreed to play something on my piano, a beautiful old 1894 Bechstein concert grand that I had grown up with, my father’s piano. Fleisher sat at the piano and carefully, tenderly, stretched each finger in turn, and then, with arms and hands almost flat, he started to play. He played a piano transcription of Bach’s “Sheep May Safely Graze,” as arranged for piano by Egon Petri. Never in its 112 years, I thought, had this piano been played by such a master—I had the feeling that Fleisher had sized up the piano’s character and perhaps its idiosyncrasies within seconds, that he had matched his playing to the instrument, to bring out its greatest potential, its particularity. Fleisher seemed to distill the beauty, drop by drop, like an alchemist, into flowing notes of an almost unbearable beauty—and, after this, there was nothing more to be said. Think about other artists you know (or know about) who’ve faced unexpected limits. How have these boundaries affected what they've made? And what about you? List and Reflect: Now, list ways that you find limits in your own artmaking/creativity. Physical, mental, emotional limits, others…? Time, space and money are some of the most common. Start there and then go deep. Consider all your limits. Conditions, boundaries, restrictions… List for about 5 minutes. Then reflect on every way your limits have gotten in the way of your art or productivity. But what if these limits have unexpected benefits? Can they help you understand why you do what you do? Can these limits help you create something remarkable? We’ll come back to this part later… Adding Boundaries Exercises: Consider how you work as an artist. What additional boundaries can you impose? Can these added boundaries inject new life into what you make? First Exercise: Impose a real, physical, imposing boundary that impacts what you do. Such as… If you’re a visual artist, you’ve lost the use of one eye, or are completely blind. If you’re a musician, one of your playing hands is no longer functional. Or you have lost your voice. If you’re a dancer or physical performance artist, you’ve lost one or more limbs. If you’re a writer, you can no longer use a language that you know well. Or you can’t use a letter of the alphabet. Or your dominant hand. If you’re an actor, you’re paralyzed from the waist up. Or…? These are examples – if you there’s a limitation that excites/scares you more, go for it. Use these examples to get ideas flowing. A lot of these limits are interchangeable between genres. Now, create something new. It can be about anything – you can start with something you’re working on already. Something about the room you're in, or someone nearby. About someone you love, where home is, what your limits are. Anything. But whatever you create needs to impose this one specific limitation. Spend about a minute deciding your limitation. Then take 4 to 8 minutes brainstorming what you want to make and how your limit could change or challenge you. If you're already stoked to dive in, you can use this time on the creating itself. Now spend 10 to 15 minutes working on your thing. Use any arts material available that speaks to you! Now hold onto that… Second Exercise: Building on the last piece, now do the genre you don’t do. It’s time to create a new piece. But you can’t use your preferred medium. It can be a variation of the last piece, or something else. But if you’re a writer, make a dance about it. If you’re a musician, express this as a painting. Endeavor into the artform that feels riskiest for you. If you feel comfortable in all genres, awesome. Then go even further outside the box – how can you make this as a culinary recipe? As a stand-up routine? As a phoned in message to the President? Again, spend about a minute choosing your genre. And 4-8 minutes brainstorming, if that's helpful. And 10-15 minutes (or as long as you want, really!) working on your thing. Then you deepen it, go further, do some revisions, even some polishing... How far can you go with this new piece? Reflect: How did that go? Think again about your limitations you wrote down earlier. Can you think of ways you could use these limits in your artform that you aren’t already? Now Share your new piece(s) with someone!

0 Comments

|

Like what I'm posting? You can leave me a tip!

$1, $10, $100, whatevs :) Heidi KraayProcess notes on a work in progress (me). This mostly contains raw rough content pulled out of practice notebooks. Occasional posts also invite you into the way I work, with intermittent notes on the hows and whys on the whats I make. Less often you may also find prompts and processes I've brought to workshops, as well as surveys that help me gather material for projects. Similar earlier posts from years ago can be found on: Archives

April 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed